While promising to save the world is increasingly part of the CEO’s job description, two new books make clear that this grandiose notion remains little more than a self-serving fantasy.

No matter how earnestly they proclaim their support for “stakeholder capitalism” – the popular promise that companies now take care of employees, communities, the planet and other “stakeholders”, not just themselves – profits still come first.

New York Times reporter Emily Flitter captures the insurmountable contradictions of stakeholder capitalism in her book, The White Wall: How Big Finance Bankrupts Black America.

In 2014, Flitter recounts, JP Morgan started making philanthropic contributions and “for-profit capital allocations” to the city of Detroit, Michigan, to “address some of Detroit’s biggest economic hurdles”, as Dimon would later phrase it. Accompanying each investment was, Flitter writes, “a media blitz that made it seem like JP Morgan bankers had galloped into a completely deserted hellscape and brought it back to life”.

Flitter reveals, from sidelining Black employees to offering Black customers inferior lending terms and investment products to promoting predatory practices in predominantly Black communities, such commitments are often little more than empty rhetoric. Empty rhetoric does nothing to address the racism that remains deeply entrenched in finance, but that doesn’t mean rhetoric is pointless – at least for executives. “The anodyne talk of diversity can be used as a shield against discussions of specific and unflattering problems,” Flitter writes, which “also helps keep the topics of racism and representation on the margins of corporate life”. The ultimate outcome of performative anti-racism is the preservation of the status quo – which is, of course, the point.

Over the next five years, the bank directed some $155m to Detroit. That’s not an insignificant amount of money – unless you compare it to JP Morgan’s own earnings or its CEO’s compensation. As Flitter points out, that $155m represented “0.03% of its profits over the same period”. Between 2015 and 2019, roughly the same window as JP Morgan’s work in Detroit, the bank’s board (which Dimon chairs) awarded Dimon more than $135m in compensation.

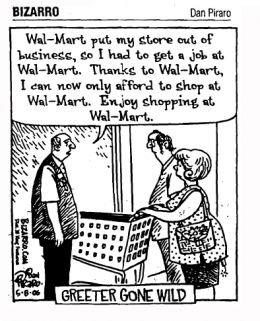

Rick Wartzman, the author of, Still Broke: Walmart’s Remarkable Transformation and the Limits of Socially Conscious Capitalism, examines Doug McMillon, Walmart’s chairman and CEO. McMillon speaks incessantly about how Walmart is committed to all of its stakeholders, particularly its 2.3 million employees. The company, Wartzman writes, “very much sees itself as part of this new wave of capitalism”.

“If there is one thing that runs as deep in Walmart’s DNA as its devotion to keeping costs down and prices low, it would have to be its antipathy toward organized labor,” Wartzman writes.

In the 1990s the company “tracked employee attitudes” to generate a “Union Probably Index” that would allow it to better target stores that might be inclined to organize. Walmart hired the elite PR firm, Edelman, to fight labor efforts; one outcome was “Working Families for Walmart”, an astroturf organization paid for by Walmart and “housed in Edelman’s Washington offices”.

Wartzman also highlights that Walmart was so afraid of the employee organizing initiative Our Walmart that the company “hired an intelligence-gathering service from Lockheed Martin, contacted the FBI, staffed up its labor hotline, ranked stores by labor activity and kept eyes on employees (and activists) prominent in the group”.

In 2015, Walmart finally announced that it would raise its minimum hourly wage to $9, with a further increase to $10 the following year. Walmart’s pay bump was a PR bonanza for the company: President Obama called to congratulate McMillon, and the company was named to Fortune’s “Change the World” list.

Yet as Wartzman’s account makes abundantly clear, the “mantle of social responsibility” that corporate and media elites have bestowed on Walmart does little for the people who depend on it the most: employees. “After all of that – after all the protests and HR focus groups, the headlines and hearings, the self-congratulatory speeches and board meetings – here’s where Walmart landed: as of summer 2022, at least half of its US hourly workers still make less than $29,000 a year, many of them a fair bit less,” Wartzman concludes.

Civil rights activist JoAnne Bland tells Wartzman after she meets with McMillon, “They know people can’t live off those wages. How much profit do you need?”

Whatever promises corporations make about fighting racism or protecting employees, these two books make clear that companies may be willing to make changes at the margins, but they still draw the line at sacrificing control or money.

The savior CEO and the empty promise of ‘stakeholder capitalism’ | JP Morgan | The Guardian

No comments:

Post a Comment