Worker militancy and strikes has recently occurred in the USA as workers went on the offensive to demand more. Workers – after working so hard and risking their lives during the pandemic – say they deserve substantial raises along with lots of gratitude. With this in mind and with myriad employers complaining of a labor shortage, many workers believe it’s an opportune time to demand more and go on strike.

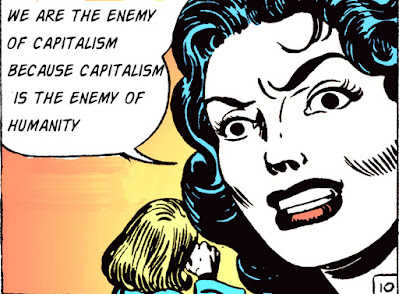

Robert Bruno, a labor relations professor at the University of Illinois, said workers have built up a lot of grievances and anger during the pandemic, after years of seeing scant improvement in pay and benefits. Bruno pointed to a big reason for the growing worker frustration: “You can definitely see that American capitalism has reigned supreme over workers, and as a result, the incentive for companies is to continue to do what’s been working for them. It’s likely that an arrogance sets in where companies think that’s going to last for ever, and maybe they don’t read the times properly.”

Professor Bruno said that in light of today’s increased worker militancy, unionized employers would have to rethink their approach to bargaining “and take the rank and file pretty seriously”. They can no longer expect workers to roll over or to strong-arm them into swallowing concessions, often by threatening to move operations overseas.

Thomas Kochan, an MIT professor of industrial relations, agreed that it was a favorable time for workers – many corporations have substantially increased pay in response to the labor shortage. “It’s clear that workers are much more empowered,” he said. “They’re empowered because of the labor shortage.” Kochan added: “These strikes could easily trigger more strike activity if several are successful or perceived to be successful.”

Some corporations are acting as if nothing has changed and they can continue corporate America’s decades-long practice of squeezing workers and demanding concessions, even after corporate profits have soared.

Deere anticipates a record $5.7bn in profits this year, more than double last year’s earnings. Deere workers complain that the company offered only a 12% raise over six years, which they say won’t keep pace with inflation, even as the CEO’s pay rose 160% last year to $16m and dividends were raised 17%.

Ten thousand John Deere workers have gone on strikeDeere’s workers voted down the company’s offer by 90% before they went on strike at 14 factories on 14 October, their first walkout in 35 years.

Kevin Bradshaw, a striker at Kellogg’s factory in Memphis, said the cereal maker was being arrogant and unappreciative. During the pandemic, he said, Kellogg employees often worked 30 days in a row, often in 12-hour or 16-hour shifts. In light of this hard work, he derided Kellogg’s contract offer, which calls for a far lower scale for new hires. “Kellogg is offering a $13 cut in top pay for new workers,” Bradshaw said. “They want a permanent two-tier. New employees will no longer receive the same amount of money and benefits we do.” That, he said, is bad for the next generation of workers. Bradshaw, vice-president of the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers union local, noted that it made painful concessions to Kellogg in 2015. “We gave so many concessions, and now they’re saying they need more,” he said. “This is a real smack in the face during the pandemic. Everyone knows that they’re greedy and not needy.”

1,400 Kellogg workers have walked out.

More than 400 workers at the Heaven Hill bourbon distillery in Kentucky have been on strike for six weeks, while roughly 1,000 Warrior Met coalminers in Alabama have been on strike since April. Hundreds of nurses at Mercy hospital in Buffalo went on strike on 1 October, and 450 steelworkers at Special Metals in Huntington, West Virginia, also walked out that day.

More than 30,000 nurses and other healthcare professionals at Kaiser Permanente on the west coast have voted to authorize a strike. Kaiser Permanente, a non-profit, had amassed $45bn in reserves and its management has proposed hiring new nurses at 26% less pay than current ones earn – which she said would ensure a shortage of nurses.

Belinda Redding, a Kaiser nurse in Woodland Hills, California, said, “We’ve been going all out during the pandemic. We’ve been working extra shifts. Our lives have been turned upside down. The signs were up all over saying, ‘Heroes Work Here’. And the pandemic isn’t even over for us, and then for them to offer us a 1% raise, it’s almost a slap in the face.” She added, “It’s hard to imagine a nurse giving her all when she’s paid far less than other nurses.”

Many non-union workers – frequently dismayed with low pay, volatile schedules and poor treatment – have quit their jobs or refused to return to their old ones after being laid off during the pandemic. In August, 4.2 million workers quit their jobs, part of what has been called the Great Resignation. Some economists have suggested this is a quiet general strike with workers demanding better pay and conditions. “People are using exit from their jobs as a source of power,” Kochan said.

No comments:

Post a Comment